Impact Accounting: Simple, impactful, and backed by science

- Emissions First Steering Committee

- Oct 15, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 17, 2025

A case study demonstrating how the City of Cambridge achieved a 2.6x reduction in emissions by prioritizing a vPPA on a more carbon intensive grid - underscoring the importance of impact accounting alongside an inventory

Introduction

In this decisive decade for global climate change, it is crucial to deploy clean energy solutions in the most efficient and impactful ways possible. As the industry has matured, some regions have grown dense pockets of clean energy while others remain reliant on fossil fuels. As a result, pushing for incremental gains in regions that are already saturated with clean energy minimizes impact. What is missing today are carbon accounting incentives to invest in clean power-hungry regions that need it most.

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) sets the primary carbon accounting standard, and has proposed draft revisions for Scope 2 accounting (emissions from energy purchases). The GHGP currently provides two methods of accounting for Scope 2 emissions: the Location Based Method (LBM) and the Market Based Method (MBM). The LBM uses average emissions factors from grids where energy consumption occurs, while the MBM reflects emissions factors from specific purchases of electricity. While both methods aim to build a credible inventory for emissions accounting, they do not measure the emissions reduction impacts of clean energy added to the grid. The GHG Project Accounting Protocol is the current guideline for measuring impact, but it does not apply to corporate-level inventory Scope 2 accounting. There is a need, as recognized by the GHGP, for a standardized methodology to assess the emissions impacts of all Scope 2 actions and interventions so that reduction efforts may be directed as effectively as possible.

The Emissions First Partnership supports and advocates for Impact Accounting (also known as “Consequential Accounting”) for Scope 2. This approach is new in application, but not new in methodology: it leans on the same marginal emissions impact approach as described in the Project Accounting Protocol (via the Guidelines for Quantifying GHG Reductions from Grid-Connected Electricity Projects). Impact Accounting offers a framework to support energy purchases that direct funding to grid regions that need it most, focusing less on paper allocation of megawatt-hours through RECs and more on counting what really matters: total carbon emitted and displaced.

How Impact Accounting works

Impact Accounting is simple. Rather than restricting load and generation to be physically nearby in order to ensure the same emissions impact, it prescribes an appropriate emissions rate to each based on time and location. Colocated sites keep the same rate, but for the vast majority of power procurement that is not colocated, Impact Accounting more accurately compares the emissions impact between the load and generation sites.

Electricity Consumption Emissions Impact = Electricity Consumption Activity * MER1

Equation 1: Impact Accounting methodology, where load is measured in megawatt-hours, and MER1 represents the weighted marginal emissions rate (operational and build) at the load location.

The key difference between the Impact Accounting method and the existing MBM is that marginal emissions rates (representing the change in grid emissions due to incremental load or generation) are used to directly express the emissions impact of energy use based on generators on the margin. This is more in line with the GHGP Project Protocol, and measures emissions reduction efforts follows the same simple structure based on the generation site’s specific emissions reduction capabilities:

Electricity Generation Emissions Impact = Electricity Generation Activity * MER2

Equation 2: Emissions reductions calculation through the Impact Accounting methodology, where generation is measured in megawatt-hours and MER2 represents the weighted marginal emissions rate at the generation site.

Following guidance from the GHGP, the Project Accounting Protocol, and the proposed Scope 2 Marginal Impact Method (MIM), marginal emissions rates should contain the weighted average between operating margin (how incremental load or generation changes the operation of existing generators), and build margin (how incremental load or generation changes the future build of generators). Both rates are available through globally-accessible, free datasets. The exact implementation is still in discussion within the GHGP AMI subgroup, but just like current inventory standards, a corporation or municipality would likely only need three simple sources of data to use the Impact Accounting method:

Load data from utility bills

Generation data from offtake contract / clean energy project

Emissions rates: publicly available MERs for both locations

Impact Accounting is already in action

Many organizations, big and small, have made clean energy purchases based on Impact Accounting. For example, the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts recently procured clean energy to reduce their Scope 2 emissions and used simple Impact Accounting to calculate their impact. At the end of 2024, the municipality announced a virtual power purchase agreement (vPPA) for ~37% of the power produced by the Prairie Solar project in Champaign County, IL.

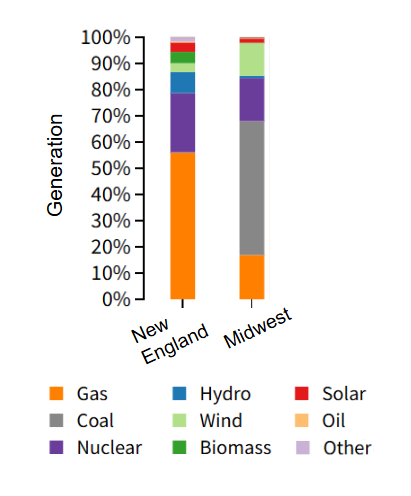

This purchase reduced Cambridge’s residential emissions, covering the average annual energy use of almost half of the city’s households. Most importantly, locating this project in Illinois allowed it to cut over 2.6 times more carbon than it would have if located in New England. The key is that in Illinois, the Prairie Solar project can produce power when dirty coal-firing generators would otherwise be producing power. On the other hand, New England is a much cleaner region - in fact, coal generation was completely decommissioned in Massachusetts over a decade ago - where solar power mostly displaces gas generators or other renewables.

Image 1: EPA’s 2023 generator supply stack by fuel type in the Midwest and New England regions, corresponding to the SRMW and NEWE eGrid regions, respectively.1

The problem: Impactful purchases are at risk

The City of Cambridge is just one example of impact-focused clean power procurement. The City was able to account for Scope 2 reductions for this purchase last year, in line with existing GHGP Scope 2 guidelines. But, alarmingly, this impact would likely never have been made if the proposed hourly matching revision to the GHGP Scope 2 methodology existed today without an impact accounting framework alongside it.

As the GHGP announced in a recent blog post, the ISB is considering moving forward with new MBM requirements including hourly generation matching within tighter market boundaries. These new requirements would not allow the City of Cambridge to claim the emission reductions associated with clean energy procured in Illinois because it falls outside the proposed market boundaries. The Impact Accounting proposal for Scope 2, which would allow the City to claim that purchase, is now under the AMI subgroup and does not yet have a clear timeline - risking a world where hourly matching is required without a corresponding impact accounting method. If that world becomes a reality, future purchases like the City of Cambridge’s will need to sacrifice tens of millions of tonnes in carbon reductions by instead purchasing power physically located near (and deliverable to) their grid region - matching their energy use based on MWh, not carbon emissions.

There is no question that the current GHGP Scope 2 proposal includes many improvements to the 2015 standard. However, if the revisions move forward without Impact Accounting included as a method of equal importance for Scope 2 reporting, clean energy development will be at risk. The reality is that GHGP-backed voluntary procurement has mobilized over 100GW of clean energy in the last decade, and the outcome of these changes will have direct impacts on what gets built and what doesn’t. If the new guidelines prevent the ability to claim emissions reductions from clean energy purchases like the City of Cambridge, it will ultimately discourage high impact procurement (such as PPAs) in exchange for less impactful, compliant purchases (like unbundled RECs).2, 3, 4

There’s still time to empower emissions reductions through Impact Accounting. The ISB has expressed support for its importance, and we can expect to see evidence of this in survey questions during the public comment period later this month. What the GHGP has proposed so far has set the groundwork for influential change. Now is the time to solidify a framework dedicated to impactful emissions reductions where we need them most.

Sources

EPA Power Profiler

Ever.Green: GHG Protocol Scope 2 Hourly Matching: Market Analysis and FAQ

Nature Climate Change: Renewable energy certificates threaten the integrity of corporate science-based targets

Companies’ Climate Goals in Jeopardy from Flawed Energy Credits